THE GREATEST BATTLE THAT YOU PROBABLY NEVER HEARD OF

I recently saw a list of the ten most important battles of the Civil War, that are ignored by historians, and the battle of Stones River was on that list. Until the 1970's I was only aware of one book ever written about Stones River. Since then there have been several important books written about the battle. Bloody Winter In Tennessee and No Better Place to Die are two that immediately come to my mind. In many, if not most Civil War history books, any reference to Stones River is left out altogether or a paragraph is allotted to the battle, if that. People with just a passing interest in the Civil War have heard of Ft. Sumter, Bull Run, Ft. Donelson, Shiloh, Antietam, Gettysburg or Vicksburg. Even the battles of Franklin and Nashville gets more attention from historians than Stones River. This battle is one of the top ten bloodiest battles of the Civil War.

Shiloh was the first bloodbath of the war and a shock to the nation. It occurred on April 6th and 7th 1862. There had been several battles prior to Shiloh. The bloodless battle of Ft. Sumter and 1st Bull Run with 2,680 casualties and Ft. Donelson with 17,398 total (US 2,331; CS 15,067). Keep in mind that twelve thousand of these casualties were Confederate prisoners that surrendered unconditionally to Grant. Bull Run was a shock to the North because it's army had been thoroughly routed, retreating in panic to Washington D.C., placing the city in danger of capture. Ft. Donelson opened the way for the fall of Nashville and would make U.S. Grant a hero. Even Grant would succumb to the euphoria in the North created from this victory and came to believe that just one more defeat could force the South to surrender. Shiloh shocked the North into the reality that this war would be long and bloody. There were more casualties at Shiloh than all the battles fought in American history to that point. Grant fell from hero to zero overnight and would have to earn the trust of the Northern people, and his superiors. all over again. They were angry at Grant because he had allowed himself to be surprised at Shiloh.

Shiloh was a learning experience for Grant. He became a modern thinking soldier after Shiloh. Grant realized that it would take a war of attrition, involving not only the defeat of Southern armies but defeating the will of the Southern people. His friend William Tecumseh Sherman had realized this much earlier than Grant. He was superintendent of a Louisiana military academy that would eventually become LSU when the war began. Sherman loved the South and Southerners but he wrote this letter to a close secessionist friend in Virginia after he resigned his position. Sherman: You people of the South don't know what you are doing. This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don't know what you're talking about. War is a terrible thing! You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people but an earnest people, and they will fight, too. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it... Besides, where are your men and appliances of war to contend against them? The North can make a steam engine, locomotive, or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on Earth—right at your doors. You are bound to fail. Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with. At first you will make headway, but as your limited resources begin to fail, shut out from the markets of Europe as you will be, your cause will begin to wane. If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail.

Shiloh was a learning experience for Grant. He became a modern thinking soldier after Shiloh. Grant realized that it would take a war of attrition, involving not only the defeat of Southern armies but defeating the will of the Southern people. His friend William Tecumseh Sherman had realized this much earlier than Grant. He was superintendent of a Louisiana military academy that would eventually become LSU when the war began. Sherman loved the South and Southerners but he wrote this letter to a close secessionist friend in Virginia after he resigned his position. Sherman: You people of the South don't know what you are doing. This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don't know what you're talking about. War is a terrible thing! You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people but an earnest people, and they will fight, too. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it... Besides, where are your men and appliances of war to contend against them? The North can make a steam engine, locomotive, or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on Earth—right at your doors. You are bound to fail. Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with. At first you will make headway, but as your limited resources begin to fail, shut out from the markets of Europe as you will be, your cause will begin to wane. If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail.

Early in the war he had suggested that it would take a vast amount of men to subdue the South and his superiors thought he had suffered a nervous breakdown. He went into seclusion for awhile and it could have meant the end of his career before it even got started. After Shiloh, Grant's enemies accused him of being drunk. Sherman would later say that their friendship was based on the fact that he had supported Grant when everyone had thought he was a drunk and Grant had supported him when everyone thought he was crazy.

The casualty numbers are almost identical between the battle of Shiloh and Stones River. There were roughly 23,000 casualties in both battles. Some accounts list the casualties as high as 24,000 men. There were 13,000 Union casualties in both battles and 10,000 Confederate casualties in both battles. To put this into perspective there were 4,000 men and women killed in Iraq from 2003 until we pulled out in 2011. The similarity, however; between these two battles end when you figure in casualty ratios. Shiloh - Forces Engaged: Army of the Tennessee and Army of the Ohio (65,085) [US]; Army of the Mississippi (44,968) [CS]. For a total of 110,053. Stones River - Forces engaged, The Army of the Cumberland (US) 43,400. The Army of Tennessee (CS) 37,317. For a total of 80,717. The two armies engaged at Shiloh had 30,000 more men than at Stones River but the casualties were virtually the same. For the North, Stones River was the costliest battle of the war when figuring casualty ratios. Gettysburg was the worse for the South. To be more specific there were 1,294 killed, 7,945 wounded, and 1,027 captured on the Confederate side at Stones River. On the Union side there were 1,730 killed, 7,802 wounded, and 3,717 captured. Making a grand total of 23,517.

At Shiloh Union casualties were 13,047 (1,754 killed, 8,408 wounded, and 2,885 missing); Grant's army bore the brunt of the fighting over the two days, with casualties of 1,513 killed, 6,601 wounded, and 2,830 missing or captured. Confederate casualties were 10,699 (1,728 killed, 8,012 wounded, and 959 missing or captured). Over the days and weeks after the battle of Stones River it is probably safe to say that at least a third of the wounded, on both sides, died of their wounds and this is probably a conservative estimate. Virtually every building of any size from Murfreesboro to Gallatin was filled with the wounded and Nashville military hospitals were overwhelmed. Although Stones River is listed as a three day battle most of the major action took place during the daylight hours of December 31st 1862, and in the time period of an hour, late on the afternoon of January 2nd 1863. Shiloh was fought during most of the daylight hours of a two day period, April 6th and 7th 1862.

|

| The Hornets Nest at Shiloh |

|

| The Hornets Nest Today |

Why then does Shiloh get all of the attention and Stones River is treated like a red headed step child by most historians? Because it was the first real bloodbath of the war. By the time Stones River was fought there had been several Shiloh's. The Seven Day's, Second Bull Run, Antietam and Fredricksburg. The war had personally affected the lives of many Americans by then. On a tactical level Stones River was a draw. Again there are similarities between Shiloh and Stones River. The Federal army at Stones River, like at Shiloh, was taken by surprise and pushed back about three miles in a state of panic to a final defensive position along the Nashville Pike and the Nashville and Chattanooga railroad. Grant would form a final defensive position with his back to the Tennessee River.

If Rosecrans lost the pike and railroad he would lose the battle because his route of escape to Nashville would be blocked and he would be caught between the rising Stones River and the Confederate army. If Grant was pushed into the river his army would be destroyed. A pocket of resistance called the Slaughter-pen bought Rosecrans the time he needed to set up a final line of defense along the pike and railroad. A pocket of resistance at Shiloh called the Hornets Nest allowed Grant enough time to set up a last line of defense along the Tennessee River. The Slaughter Pen at Stones River was held by men under the command of James S. Negley and Phillip Sheridan. Nashville's Ft. Negley is named after Negley. He would perform well at Stones River but on the second day at Chickamauga he would be relieved of command after the disastrous Union defeat. Negley was later acquitted of any wrongdoing but he would never return to active command. Most people are not aware that the name of Ft. Negley was officially changed to Ft. Harker after the battle of Kennesaw Mountain in honor of General Charles Harker who was killed in that battle. The name Ft. Negley stuck however and the rest is history.

|

| Ft. Negley |

|

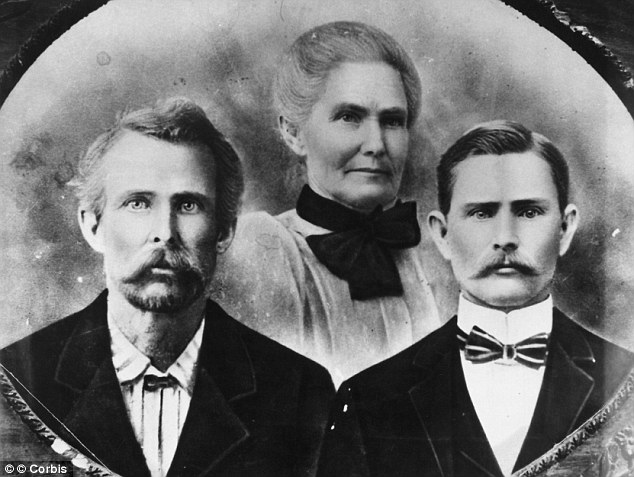

| My mother Donie Belle Brown Segroves with her boyfriend at the time |

Sheridan would go on to be one of the North's greatest fighting generals, especially in the late stages of the war in the east commanding Grant's cavalry. He would turn sure defeat into a stunning victory over Jubal Early at Cedar Creek. Sheridan devastated the Shenandoah Valley in much the same way that Sherman destroyed the South in his March to the Sea. He defeated General Pickett's forces at Five Forks on April 2nd 1865 forcing the evacuation of Petersburg. This victory resulted in the fall of Richmond the next day and set in motion events that led to the eventual surrender of Lee at Appomattox a week later on April 9th.

By 1866 he was fighting Indians in Texas. In January 1869 Comanche Chief Tosawi struck his chest forcibly and said "Me, Tosawi; me good Injun" Sheridan supposedly replied, "The only good Indians I ever saw were dead." thus coining the phrase that the only good Indian is a dead Indian. Sheridan vehemently denied ever saying this. However he did urge the destruction of the buffalo herds saying that if they disappeared the Indians would disappear. By 1885 they were nearly gone and the Indians were going hungry. "We took away their country and their means of support, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease and decay among them and it was for this and against this they made war. Could anyone expect less? He would eventually be appointed to command the United States Army in 1883 and would hold this job until shortly before his death in 1888.

|

| General Phillip Sheridan |

|

| Sheridan's horse Rienzi at the Smithsonian |

Generals Sheridan and Negley were under the command of General Alexander McCook who commanded the Union right wing at Stones River. All night of December 30th 1863 Sheridan and Negley heard the ominous sounds of the Confederates moving troops into position for an attack early the next morning. They notified McCook in person but he wasn't concerned. He dismissed them and ordered the two officers to return to their men. When they returned orders were issued for their men to sleep fully clothed and under arms ready to fight at a moments notice. The attack began at the crack of dawn on December 31st 1862. The rebels of Hardee's Corps were lined up two lines deep along present day Cason Lane. McCook's exposed right flank was camped on either side of Gresham Lane where it intersects with Franklin road. McCook had ordered fires built to the right of his line in order to deceive the Rebels into believing the Union line extended farther down Franklin road than it actually did. When the Confederate attack began this would backfire on the Union Army. The Confederates easily overlapped the Union right.

The Union army rose early and began cooking their breakfast. They were unaware that a full scale Confederate attack was rolling like a tidal wave toward their position, concealed by the low hanging morning mists that are common in this area during the winter. The screaming rebels were on top of them before they could react. Men were shot dead with coffee pots in their hands. The following is an account of this phase of the battle. "The comfort of warming chilled fingers and toes and drinking a grateful cup of hot coffee outweighed for the moment any consideration of danger.... As all was so quiet, not a shot having been fired, I...walked out until the enemy's breastworks were in view and there, sure enough,...a succession of long lines of Gray were swarming over the Confederate breastworks and sweeping towards us but not yet within gun shot range. Then came chaos. Men began to run in every direction, for no one knew where to go. Our only salvation was to lie flat as possible, for the air seethed with the 'Zip' of bullets.... It reminded me of the passage of a swarm of bees. Bullets plowed little furrows around us, throwing up grass and soil into our faces or over our bodies, and others struck with a dull 'thud' into some poor unfortunate soul". The Union Army was routed. The right wing was driven back to the area of the modern day Avenue shopping mall. It was in this area that General Joshua Sill was killed. Sill was a close friend of Sheridan and he would later name Ft. Sill Oklahoma after him.

|

| General Joshua Sill |

|

| The Avenue Mall - Scene of heavy fighting on the morning of December 31, 1862 |

|

| Canteen found with bloodstains at Stones River |

The following is Sam Watkins account of the fighting, from his book Co. Aytch, near the Slaughter-Pen along the Wilkinson Pike, which is now called Manson Pike. We were ordered forward to the attack. We were right upon the Yankee line on the Wilkerson turnpike. The Yankees were shooting our men down by scores. A universal cry was raised, "You are firing on your own men." "Cease firing, cease firing," I hallooed; in fact, the whole skirmish line hallooed, and kept on telling them that they were Yankees, and to shoot; but the order was to cease firing, you are firing on your own men. Captain James, of Cheatham's staff, was sent forward and killed in his own yard. We were not twenty yards off from the Yankees, and they were pouring the hot shot and shells right into our ranks; and every man was yelling at the top of his voice, "Cease firing, you are firing on your own men; cease firing, you are firing on your own men." Oakley, color-bearer of the Fourth Tennessee Regiment, ran right up in the midst of the Yankee line with his colors, begging his men to follow. I hallooed till I was hoarse, "They are Yankees, they are Yankees; shoot, they are Yankees." The crest occupied by the Yankees was belching loud with fire and smoke, and the Rebels were falling like leaves of autumn in a hurricane. The leaden hail storm swept them off the field. They fell back and re-formed. General Cheatham came up and advanced. I did not fall back, but continued to load and shoot, until a fragment of a shell struck me on the arm, and then a minnie ball passed through the same paralyzing my arm, and wounded and disabled me. General Cheatham, all the time, was calling on the men to go forward, saying, "Come on, boys, and follow me."

The impression that General Frank Cheatham made upon my mind, leading the charge on the Wilkerson turnpike, I will never forget. I saw either victory or death written on his face. When I saw him leading our brigade, although I was wounded at the time, I felt sorry for him, he seemed so earnest and concerned, and as he was passing me I said, "Well, General, if you are determined to die, I'll die with you." We were at that time at least a hundred yards in advance of the brigade, Cheatham all the time calling upon the men to come on. He was leading the charge in person. Then it was that I saw the power of one man, born to command, over a multitude of men then almost routed and demoralized. I saw and felt that he was not fighting for glory, but that he was fighting for his country because he loved that country, and he was willing to give his life for his country and the success of our cause. He deserves a wreath of immortality, and a warm place in every Southron's heart, for his brave and glorious example on that bloody battlefield of Murfreesboro. Yes, his history will ever shine in beauty and grandeur as a name among the brightest in all the galaxy of leaders in the history of our cause. Now, another fact I will state, and that is, when the private soldier was ordered to charge and capture the twelve pieces of artillery, heavily supported by infantry, Maney's brigade raised a whoop and yell, and swooped down on those Yankees like a whirl-a-gust of woodpeckers in a hail storm, paying the blue coated rascals back with compound interest; for when they did come, every man's gun was loaded, and they marched upon the blazing crest in solid file, and when they did fire, there was a sudden lull in the storm of battle, because the Yankees were nearly all killed. I cannot remember now of ever seeing more dead men and horses and captured cannon, all jumbled together, than that scene of blood and carnage and battle on the Wilkerson turnpike. The ground was literally covered with blue coats dead; and, if I remember correctly, there were eighty dead horses.

By this time our command had re-formed, and charged the blazing crest. The spectacle was grand. With cheers and shouts they charged up the hill, shooting down and bayoneting the flying cannoneers, General Cheatham, Colonel Field and Joe Lee cutting and slashing with their swords. The victory was complete. The whole left wing of the Federal army was driven back five miles from their original position. Their dead and wounded were in our lines, and we had captured many pieces of artillery, small arms, and prisoners. When I was wounded, the shell and shot that struck me, knocked me winding. I said, "O, O, I'm wounded," and at the same time I grabbed my arm. I thought it had been torn from my shoulder. The brigade had fallen back about two hundred yards, when General Cheatham's presence reassured them, and they soon were in line and ready to follow so brave and gallant a leader, and had that order of "cease firing, you are firing on your own men," not been given, Maney's brigade would have had the honor of capturing eighteen pieces of artillery, and ten thousand prisoners. This I do know to be a fact.

As I went back to the field hospital, I overtook another man walking along. I do not know to what regiment he belonged, but I remember of first noticing that his left arm was entirely gone. His face was as white as a sheet. The breast and sleeve of his coat had been torn away, and I could see the frazzled end of his shirt sleeve, which appeared to be sucked into the wound. I looked at it pretty close, and I said "Great God!" for I could see his heart throb, and the respiration of his lungs. I was filled with wonder and horror at the sight. He was walking along, when all at once he dropped down and died without a struggle or a groan. I could tell of hundreds of such incidents of the battlefield, but tell only this one, because I remember it so distinctly.

ROBBING A DEAD YANKEE

In passing over the battlefield, I came across a dead Yankee colonel. He had on the finest clothes I ever saw, a red sash and fine sword. I particularly noticed his boots. I needed them, and had made up my mind to wear them out for him. But I could not bear the thought of wearing dead men's shoes. I took hold of the foot and raised it up and made one trial at the boot to get it off. I happened to look up, and the colonel had his eyes wide open, and seemed to be looking at me. He was stone dead, but I dropped that foot quick. It was my first and last attempt to rob a dead Yankee. After the battle was over at Murfreesboro, that night, John Tucker and myself thought that we would investigate the contents of a fine brick mansion in our immediate front, but between our lines and the Yankees', and even in advance of our videts. Before we arrived at the house we saw a body of Yankees approaching, and as we started to run back they fired upon us. Our pickets had run in and reported a night attack. We ran forward, expecting that our men would recognize us, but they opened fire upon us. I never was as bad scared in all my whole life, and if any poor devil ever prayed with fervency and true piety, I did it on that occasion. I thought, "I am between two fires." I do not think that a flounder or pancake was half as flat as I was that night; yea, it might be called in music, low flat.

It was in this area that the rebels finally met stiff resistance from the divisions of Sheridan and Negley. They were ready to fight and weren't surprised like the others. Many of the men who fought here were from Chicago and said that the blood and gore reminded them of the slaughter pens of the Chicago meat packing district. Their defense was helped by limestone outcroppings that served as natural rifle pits. The battle in this area began around 1000 AM and lasted to around 1200 PM. Sheridan and Negley were surrounded on three sides until the order to withdraw was given. They pulled back to the the Nashville Pike and railroad. The Slaughter-pen bought Rosecrans enough time to organize this strong defensive line that would eventually save the Union army. As at Shiloh the Confederates wasted precious time concentrating on the Slaughter-pen instead of bypassing it. A young 18 year old Lieutenant on the staff of Phillip Sheridan, named Arthur MacArthur, would learn a valuable lesson here. He would be the father of Douglas MacArthur and would go on to win the Medal of Honor at Missionary Ridge. MacArthur also helped to save the Union Army at the battle of Franklin where he would be severely injured. After the war he commanded men in the Indian wars and the Philippine Insurrection. MacArthur rose to the rank of Major General and because of the lesson learned at Stones River he was never surprised in battle. This was a lesson that he never passed on to his son Douglas. He would allow his Air Force to be destroyed on the ground at Clark Field a day after Pearl Harbor and his army to be ambushed near the Yaloo River by the Chinese in the Korean War. These two incidents contributed to the two worst defeats in American history.

|

| The slaughter pen |

|

| The slaughter pen |

|

| Arthur MacArthur |

The Confederates maintained momentum as long as they were in the woods and cedar breaks. Because of the terrain the Confederates couldn't bring their artillery to bear on the retreating Union soldiers. In the Civil War you could only shoot at what you could see. The same held true for the Union forces. Thomas Corps was protecting the highway and pike along with the remnants of McCook's men. There was a wide open cotton field near the pike that became a killing field for Thomas artillery and infantry. Most of the artillery was lined up along the high ground where the present day National Cemetery is. When the Confederates came out of the woods they were slaughtered and their attack was ultimately stopped. On the Union left the brigade of General William Hazen defended Hells Half Acre or the Round Forest as it was called. This was the only Union position that held during the 1st day of battle on December 31st.

During the day Hazen fought off four Confederate Brigades. The Hazen's brigade monument was built by the Union Army just after the battle making it the oldest Civil War memorial in the country. During the battle Rosecran's and his staff were riding back and forth from Thomas position to Hazen's position along the railroad when a Confederate cannonball decapitated Rosecran's chief of staff Colonel Julius Garesche. The same ball took off the legs of a Sergeant and passed through the neck of a horse. Rosecrans would finish the battle with the blood and brains of Garesche splattered all over his uniform. That night Rosecran's held a council of war at his headquarters where the rock quarry is now located on the Nashville Pike. There is a story that General Thomas was napping in the corner of the cabin when Rosecrans began talking about retreat back to Nashville. Thomas woke up long enough to say, this army doesn't retreat, and then went back to sleep.

|

| The Hazen's Brigade Monument - Hells Half Acre |

|

| Confederates reenactors near the Round Forrest |

|

| Looking toward the Round Forrest |

|

| Looking toward the Round Forest |

|

| The Round Forest |

|

| The battle near the Nashville Pike |

|

| Position of Thomas Artillery on High Ground Along The Nashville Pike And Railroad |

|

| Russell Qualls at Stones River National Cemetery |

|

| Grave of a 16 year old boy |

|

| Thomas Corps along the Nashville Pike and railroad |

|

| Lt. Colonel Julius Peter Garasche |

|

| The death of Colonel Garasche |

|

| Garasche's headless body fell here after riding about twenty paces erect in the saddle |

|

| Union soldiers searching the battlefield for Garasche's body |

|

| George Thomas |

There was very little fighting on New Years day 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation was signed by Lincoln on this day. The armies used the time to tend to the wounded and dig trenches along with throwing up breastworks. On January 2nd, late in the afternoon, Bragg used former Vice President John C. Breckenridge's Orphan Brigade to dislodge the Union army from the high ground across from McFadden's Ford on Stones River. The Confederate attack succeeded in forcing the Union Army to retreat. If the rebels had gone no further they would have achieved their objective, Flushed with success they unwisely followed the retreating Union soldiers right in to a horrific artillery ambush. Union artillery Captain John Mendenhall had 45 cannon lined hub to hub along the high ground on the opposite side of the river above McFadden's Ford with 12 cannon a mile southwest providing enfilading fire. As the rebels neared the riverbank the Union artillery opened up on the Confederate Army producing 1800 casualties in less than an hour. The Union Army counterattacked regaining the lost ground. Bragg's army was reduced to 20,000 men and thinking that the Union army would be receiving reinforcements he decided to retreat to the Duck River line on January 3rd, establishing his headquarters at Tullahoma, where he would remain until June 1863. The following is an account of a Union official who visited the battlefield of Stones River just after the battle.

NASHVILLE, Saturday, Jan. 10, 1863.

I have just returned from a three days' visit to the battle-field of Stones River, or, as some term it, Murfreesboro. The battle was fought some four miles this side of the town, and the ground embraced cotton, corn and wheat fields, a grove of forest trees, and the banks of Stones River, a small stream, which winds around the town, easily fordable at this season. The fields on which the fight took place are for the most part level. The ground where the centre, under THOMAS, first engaged the enemy, is a dense cedar forest, with a road through it, leading out into a cotton-field. The largest number of graves I saw together during my ride over the battle-field was 93. On a board near by was the following written in pencil: "This cemetery contains the bodies of officers and men of the Fifteenth, Sixteenth, Eighteenth and Nineteenth United States Regulars; it is earnestly requested that no one will molest them or make additions thereto."

The field and woods bear marks of heavy firing -- scarcely a tree that has not its branches lopped off, or its trunk scarred by the missiles of lead and iron rained among them; while on the ground, imbedded in the half-frozen mud, lie unexploded shells, cannon balls, canister, grape and bullets of every description. In one part of the field was a dismantled Napoleon gun left, or captured from the rebels. A large number of broken and worthless guns were lying about, evidently injured by the owners, as an excuse to quit the field. At the time I visited the ground -- four days after the battte -- nearly all the dead had been buried, save four poor fellows, who, with their guns beside them, lay behind a fence, having escaped the notice of the burial parties. I heard of some other of our dead who lay in a shattered log house, whither they had gone for shelter, and had there died of their wounds. The rebel dead were buried by our men in trenches, and no estimate can be accurately made as to their number, though it is believed that they largely outnumber ours.

On one spot one hundred and fifty dead rebels were counted, lying in heaps, as they had been shot down by our artillery. The field is strewn with dead horses; on one spot the horses of an entire battery were killed. While our troops were fighting the enemy in front, the rebel Gen. WHEELER and his cavalry were attacking and destroying our supply trains on the Murfreesboro Pike; and for two days our men suffered terribly from hunger. The incorrigible Nineteenth Illinois, however -- always fertile in expedients -- noted every particularly fine horse that was shot, and, after bleeding the animal, would proceed to cut steaks from him, which they cooked and ate with much relish. They aver that there is little difference between beef and horse meat, if properly cooked. The Eleventh Kentucky Regiment behaved with great gallantry, and, in recognition of their effective services, Gen. ROSECRANS has given the whole regiment a furlough for thirty days.

Our wounded men were removed from the field, and now occupy the hospitals in Nashville, some 2,500 having already been provided for. The First Presbyterian, First Baptist and Methodist churches have all been taken for hospitals, to the intense disgust of the disloyal congregations who formerly assembled there. The National wounded, are also quartered in houses along the Murfreesboro Pike -- those who were unable to be carried to Nashville. Owing to the depredations committed upon our trains at Lavergne, and the known disloyalty of its population. Gen. ROSECRANS ordered the place destroyed, and but one house -- that an hospital -- marks the spot where stood this village. The indications of rebel outrages upon our trains are visible along the road from Lavergne to Murfreesboro. Two hundred wagons were burned near the former place by WHEELER, and the road is strewn with half-buried wheels, axles, tires and mules; many of the latter were burned while in harness. This ruffian, WHEELER, destroyed everything designed for our army; even hospital stores were not respected. Ambulances were destroyed, and the occupants pitched out upon the road.

|

| Trenches dug on the night of the 31st |

|

| Union counterattack at McFadden's Ford |

Stones River was important for several reasons. Strategically the Union Army captured Murfreesboro which would become a major rail head for materials that would supply the Union army as it advanced along the Nashville-Chattanooga corridor and later as the army moved from Chattanooga to Atlanta. Psychologically it lifted the morale of the Northern people during their darkest year of the war. Just two weeks earlier the North had suffered it's worst defeat at Fredricksburg. Then there would be Burnside's infamous Mud March in January and Lee's greatest victory at Chancellorsville in May. The North would not have anything to cheer about until early in July 1863 when the news came of three simultaneous victories by Rosecran's over Bragg's Duck River line, Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Stones River was the only bright spot with the exception of Antietam and Perryville for nearly a year. Antietam and Stones River were strategic victories for the Union but tactical draws and incredibly bloody. The Union army at Murfreesboro would be unable to fight for six months because of the losses it suffered at Stones River. Lincoln said it best in a letter he later wrote to Rosecran's when he was relieved in disgrace after his defeat at Chickamauga. "You gave us a hard earned victory, which had there been a defeat instead, the nation could scarcely have lived over".

On the last day of Lincoln's life April 14th 1865 he had a final cabinet meeting in which General Grant was present. They were all waiting on the good news that Confederate General Joseph Johnston had surrendered to General Sherman. Lee had surrendered five days earlier at Appomattox and Johnston would not surrender until April 26th. Lincoln talked about a recurring dream he had the night before. "The usual dream which he had preceding nearly every great and important event of the war. Generally the news had been favorable which preceded this dream, and the dream itself was always the same ... [he said that] he seemed to be in some singular, indescribable vessel, and that he was moving with great rapidity towards an indefinite shore; that he had this dream preceding Sumter, Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg, Stones River, Vicksburg, Wilmington, etc." Grant broke in to say, "Stones River was certainly no victory, and he knew of no great results which followed from it." Lincoln took Grants statement in good humor. However that might be, he replied, his dream preceded that fight. "I had this strange dream again last night, and we shall, judging from the past, have great news very soon. I think it must be from Sherman." Lincoln would be shot later that night at Ford's theater.

|

| Stones River National Cemetery 1866 |

|

| Black Soldiers Collecting The Remains Of Soldiers Killed At Cold Harbor For Burial In A National Cemetery |

|

| Statue in front of Rutherford County Court House honoring the Confederate soldiers who fought at Stones River |

|

| Stones River National Park circa 1930's |

|

| Stones River Battlefield circa 1930's |

|

| A Medal Of Honor Won At Stones River |

There was very little fighting on New Years day 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation was signed by Lincoln on this day. The armies used the time to tend to the wounded and dig trenches along with throwing up breastworks. On January 2nd, late in the afternoon, Bragg used former Vice President John C. Breckenridge's Orphan Brigade to dislodge the Union army from the high ground across from McFadden's Ford on Stones River. The Confederate attack succeeded in forcing the Union Army to retreat. If the rebels had gone no further they would have achieved their objective, Flushed with success they unwisely followed the retreating Union soldiers right in to a horrific artillery ambush. Union artillery Captain John Mendenhall had 45 cannon lined hub to hub along the high ground on the opposite side of the river above McFadden's Ford with 12 cannon a mile southwest providing enfilading fire. As the rebels neared the riverbank the Union artillery opened up on the Confederate Army producing 1800 casualties in less than an hour. The Union Army counterattacked regaining the lost ground. Bragg's army was reduced to 20,000 men and thinking that the Union army would be receiving reinforcements he decided to retreat to the Duck River line on January 3rd, establishing his headquarters at Tullahoma, where he would remain until June 1863. The following is an account of a Union official who visited the battlefield of Stones River just after the battle.

NASHVILLE, Saturday, Jan. 10, 1863.

I have just returned from a three days' visit to the battle-field of Stones River, or, as some term it, Murfreesboro. The battle was fought some four miles this side of the town, and the ground embraced cotton, corn and wheat fields, a grove of forest trees, and the banks of Stones River, a small stream, which winds around the town, easily fordable at this season. The fields on which the fight took place are for the most part level. The ground where the centre, under THOMAS, first engaged the enemy, is a dense cedar forest, with a road through it, leading out into a cotton-field. The largest number of graves I saw together during my ride over the battle-field was 93. On a board near by was the following written in pencil: "This cemetery contains the bodies of officers and men of the Fifteenth, Sixteenth, Eighteenth and Nineteenth United States Regulars; it is earnestly requested that no one will molest them or make additions thereto."

The field and woods bear marks of heavy firing -- scarcely a tree that has not its branches lopped off, or its trunk scarred by the missiles of lead and iron rained among them; while on the ground, imbedded in the half-frozen mud, lie unexploded shells, cannon balls, canister, grape and bullets of every description. In one part of the field was a dismantled Napoleon gun left, or captured from the rebels. A large number of broken and worthless guns were lying about, evidently injured by the owners, as an excuse to quit the field. At the time I visited the ground -- four days after the battte -- nearly all the dead had been buried, save four poor fellows, who, with their guns beside them, lay behind a fence, having escaped the notice of the burial parties. I heard of some other of our dead who lay in a shattered log house, whither they had gone for shelter, and had there died of their wounds. The rebel dead were buried by our men in trenches, and no estimate can be accurately made as to their number, though it is believed that they largely outnumber ours.

On one spot one hundred and fifty dead rebels were counted, lying in heaps, as they had been shot down by our artillery. The field is strewn with dead horses; on one spot the horses of an entire battery were killed. While our troops were fighting the enemy in front, the rebel Gen. WHEELER and his cavalry were attacking and destroying our supply trains on the Murfreesboro Pike; and for two days our men suffered terribly from hunger. The incorrigible Nineteenth Illinois, however -- always fertile in expedients -- noted every particularly fine horse that was shot, and, after bleeding the animal, would proceed to cut steaks from him, which they cooked and ate with much relish. They aver that there is little difference between beef and horse meat, if properly cooked. The Eleventh Kentucky Regiment behaved with great gallantry, and, in recognition of their effective services, Gen. ROSECRANS has given the whole regiment a furlough for thirty days.

Our wounded men were removed from the field, and now occupy the hospitals in Nashville, some 2,500 having already been provided for. The First Presbyterian, First Baptist and Methodist churches have all been taken for hospitals, to the intense disgust of the disloyal congregations who formerly assembled there. The National wounded, are also quartered in houses along the Murfreesboro Pike -- those who were unable to be carried to Nashville. Owing to the depredations committed upon our trains at Lavergne, and the known disloyalty of its population. Gen. ROSECRANS ordered the place destroyed, and but one house -- that an hospital -- marks the spot where stood this village. The indications of rebel outrages upon our trains are visible along the road from Lavergne to Murfreesboro. Two hundred wagons were burned near the former place by WHEELER, and the road is strewn with half-buried wheels, axles, tires and mules; many of the latter were burned while in harness. This ruffian, WHEELER, destroyed everything designed for our army; even hospital stores were not respected. Ambulances were destroyed, and the occupants pitched out upon the road.

The following are excerpts from two articles that appeared in the Cleveland Herald in April of 1863.

Night on the Battle Field of Stones River---The Old Year Out---the New year's Ride

Carefully, driver, carefully! Let the hard iron of the wheels roll slowly over the pounded stone of the [Nashville] pike. The young soldier still lives. His breath is short, but we may yet reach the hospital nere he dies. Guide steadily past the shattered wagons---round the heaps of dead horses---through the long rows of corpses; watch that no foot of a horse jars against the fallen dead---the heroes of the last day of 1862---resting now, where they fell, or where friends have laid them. Here they lie in rows of miles, sleeping out the old year. On the last day of Sixty-two they stood for their country and for Freedom. At its midnight hour they sleep, no more to awake to war's ringing bugle call.

Well might thoughts of the old year and of eternity crowd upon the mind of the soldier whose duty to the wounded living brought him across that vast field of the ghastly dead---this night so clear and frosty---the last of December.

The story, as he told it---he, a private...---let me tell it.

That awful night! Words will not paint it, yet may give some faint idea of what sad experience a day of carnage brings.

At 9 o'clock of the evening of December 31st, an ambulance left one of the hospitals of Rosecrans' army, moving in the direction of Nashville. Two soldiers lay upon the carriage. The life blood of one, following the passage of a minnie ball through the breast, was oozing out from the right lung, staining the blankets beneath. The other, suffering from a crushing shot through the left leg...[was] scarcely conscious. Along with the carriage walked [the] private---going to care for his wounded companions.

Three miles along the stony pike...lay their route. Here an artillery wagon had been swept by a bursting shell---its gun dismounted, its wheels shattered, the horses and men fallen together, lay mixed as they had gone down. Still tangled in the harness hitched to the caissons, lay the hind parts of a horse, his breast and forelegs swept away, while the lifeless body of an artillerist rested with an arm over the dismounted gun...

Yonder a cavalryman had fallen, his drawn saber reflecting in the moonlight against the dark earth where he lay; and beside him his comrade and his horse, all keeping the same silent watch of death.

The sharp frost of a clear night spread its white drapery over the clothes of the dead---on the locks [of hair]...gathered its icy breath, offering alike to all a common shroud...

All along the road for more than two miles, were these scenes of horror met by the weary soldier. Still on rolled the ambulance---past broken wagons---lost muskets and dismounted artillery, to the great general hospital of the fourth division.

Here after midnight lay the wounded and dying, covering an acre of ground...of which every room was filled, every outhouse crowded, the very floor wet with blood. Close by lay a man with an arm gone---next to him one with a leg smashed---there a part of a face was shot away...Yet all those hundreds living, many waiting the dressing of their wounds with patience.

Our two soldier boys were taken from the ambulance into the building, and with hundreds of others closed no eyes to sleep that last December night.

The morning sun of Jan. 1st, 1863 rose upon a day as clear as ever dawned. Surgeons came that morning, and looked upon the one wounded in the breast...whispering to the private that "He will die."

At 9 o'clock that morning [another] soldier and the one wounded through the breast were put into a strong army wagon...and, with the private and...driver, started over the pike for Nashville. Just as they reached the bridge the enemy, sweeping round our right, had brought a battery to bear upon the bridge.

Fearfully whirled our driver on, as if careless of the dying men in his charge, and only seeking safety in flight. Full three miles the race continued, when on came dashing a battalion of rebel Wheeler's cavalry...yelling and firing on the teamster and the wounded. The breast-wounded soldier lay gasping and ordering the other soldier, who held his footless leg in one hand...to shoot the driver if he did not stop, that they might surrender, before they were murdered by the now near foe. But on, on heedless alike of threats and enemy, dashed the driver...Nine miles over the stony road had the race continued. The determined driver had brought his team through, and escaped with the suffering load.

At 9o'clock that evening they were taken from the wagon...and placed upon good cots, receiving close attention at the hands of skillful surgeons.

Charles Stansell, the driver, and the soldiers he transported survived their ordeal at Stones River. Later, Stansell was killed in a fight. He is buried at the Hazen Brigade Monument on the battlefield at the request of those he saved. The soldier who had been wounded in the breast at Stones River wrote the following tribute for the Cleveland Herald.

Death of a Brave Soldier

The untimely death of Charles Stansell, Co. G 41st Ohio, deserves from me more than a passing notice.

Charles Stansell was the fearless driver of a four horse team from Murfreesboro to Nashville...when Lieut. Wolcott and myself were being conveyed to a hospital...He...would not stop, but rushed on, heedless of our protests and threats...thus saving our team, our wagon, and our lives, all of which would have been sacrificed had we fallen into the hands of the rebels.

Comments

Post a Comment