THE INCREDIBLE STORY OF JACOB MILLER

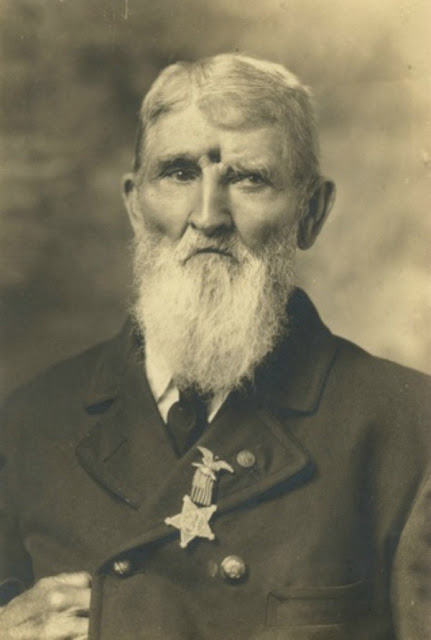

Jacob Miller, who was born in 1840 and died in 1917, was a private in Co. G of the 113th Illinois Infantry at the battle of Vicksburg, Mississippi. During the month of May 1863 Union forces tried to storm Confederate lines around the city of Vicksburg on several occasions. One of the Confederate redoubts was taken by volunteers. It would become known as the “charge of the volunteer storming party.” One of those who volunteered was Jacob Miller. During this charge on May 22, 1863, Miller was cited for his audacious courage and awarded the Medal of Honor.

Millers unit would eventually end up at the battle of Chickamauga near Chattanooga which was fought on September 19th and 20th 1863. Chickamauga was the 2nd worst battle of the Civil War just behind Gettysburg. Gettysburg had 51,000 casualties in three days as opposed to the 40,000 casualties at Chickamauga in two days. Ironically many of the Confederates that fought at Gettysburg would also fight at Chickamauga in Longstreet's Corps. Unlike Gettysburg, however: Chickamauga was a disastrous defeat for Union forces. At Chickamauga Jacob Miller was shot right between the eyes on September 19th. He immediately fell to the ground and was left for dead by his comrades. Miraculously Jacob survived and lived another 54 years to tell the tale. The following is his story printed in The Daily News — Joliet, Illinois. Wednesday, June 14, 1911.

“After being shot, I was left for dead when my company fell back from that position. When I came to my senses some time after, I found I was in the rear of the Confederate line.” Jacob was only able to get up using his rifle as a crutch and made his way through the Confederate lines to an old back road. “I suppose I was so covered with blood that those that I met, did not notice that I was a Yank. By this time my head was swelled so bad it shut my eyes and I could see to get along only by raising the lid of my right eye with my finger and looking ahead, then going on till I ran afoul of something, then would look again and so on.” He became so weary that he laid down on the side of the road. Some stretcher bearers saw him and carried him to the field hospital. There “A hospital nurse came and put a wet bandage over my wound and around my head and gave me a canteen of water. The surgeons examined my wound and decided it was best not to operate on me and give me more pain as they said I couldn’t live very long, so the nurse took me back into the tent. I slept some during the night. The next morning, the doctors came around to make a list of the wounded and said they were sending all the wounded to Chattanooga, Tennessee. But they told me I was wounded too bad to be moved.”

The doctors told Jacob if he was left behind he would be exchanged later. The very thought of being a prisoner of war was repulsive to Jacob. “I made up my mind, as long as I could, to drag one foot after another. I got a nurse to fill my canteen with water so I could make an effort in getting as near to safety as possible. I got out of the tent without being noticed and got behind some wagons that stood near the road till I was safely away — having to open my eye with my finger to take my bearings on the road. I went away from the boom of cannon and the rattle of musketry. I worked my way along the road as best I could. At one time, I got off to the side of the road and bumped my head against a low hanging limb. The shock toppled me over, I got up and took my bearings again and went on as long as I could drag a foot, then lay down beside the road.” Jacob didn't lay there long. Wagons began to pass by that were taking the wounded to Chattanooga. “One of the drivers asked if I was alive and said he would take me in, as one of his men had died back aways, and he had taken him out.” Jacob lost consciousness once he was inside the wagon..

He awoke the next day after arriving in Chattanooga and found himself in a long building, “lying with hundreds of other wounded on the floor almost as thick as hogs in a stock car. Some were talking, some were groaning. I raised myself to a sitting position, got my canteen and wet my head. While doing it, I heard a couple of soldiers who were from my company. They could not believe it was me as they said I was left for dead on the field. They came over to where I was and we visited together till an order came for all the wounded that could walk to start across the river on a pontoon bridge to a hospital. We were to be treated and taken to Nashville. I told the boys if they could lead me, I could walk that distance. Jacob, along with his his friends made their way to the bridge, finding a long line of troops and artillery crossing over. Just before sundown they were able to cross over to the other side of the river.

“When we arrived across, we found our company teamster, who we stopped with that night. He got us something to eat. It was the first thing I had tasted since Saturday morning, two days earlier. After we ate, we lay down on a pile of blankets, each fixed under the wagon and rested pretty well as the teamsters stayed awake till nearly morning to keep our wounds moist with cool water from a nearby spring. The next morning, we awoke to the crackling of the camp fire. We got a cup of coffee and a bite of hard tack and fat meat to eat. While eating, an orderly rode up and asked if we were wounded. If so, we were to go back along the road to get our wounds dressed, so we bid the teamsters good-bye and went to get our wounds attended to. That was the first time my wound was washed and dressed by a surgeon.”

At this point Jacob and his friends received supplies, “a few crackers, some sugar, coffee, salt and a cake of soap.” They were then sent by wagon to Bridgeport, Alabama. The wagon ride was very painful. “The jolting hurt my head so badly I could not stand it, so I had to get out. My comrades got out with me and we went on foot.” Jacob and his friends walked sixty miles to Bridgeport. It took four days to get there. After a while Jacob was finally able to open his right eye without using his fingers.

Arriving in Bridgeport they caught a train to Nashville, Tennessee. The struggle of the trip and the pain from his wound ended up taking a toll on Jacob. He was in a state of total exhaustion. “The sand had run out with me for the time being."

Jacob remembered sitting in a tub of warm water in a hospital in Nashville. From there he was transported to a hospital in Louisville, Kentucky. The hospital in Louisville is where my own great great grandfather Isaac Mayfield of the 13th Kentucky Infantry died of pneumonia on December 13, 1862. Jacob was taken from Louisville to another hospital in New Albany, Indiana. He wanted the bullet to be removed from his head. “In all the hospitals I was in, I begged the surgeons to operate on my head but they all refused.”

Jacob suffered for nine months until he finally talked two doctors into operating on him and they took out the musket ball. Jacob was in the hospital until his enlistment was up on September 17, 1864.

It was later discovered that there was more than a musket ball in Jacob's head. “Seventeen years after I was wounded, a buck shot dropped out of my wound. And thirty one years after, two pieces of lead came out.”

He was asked later how he could tell his story with such clarity after so many years had passed. “I have an everyday reminder of it in my wound and constant pain in the head, never free of it while not asleep. The whole scene is imprinted on my brain as with a steel engraving.”

Jacob wanted the readers of the newspaper article to know that he wasn't complaining. He said that “The government is good to me and gives me $40.00 per month pension.” Forty dollars a month in the late 1800's would probably be between seven and eight hundred dollars a month in today's currency.

Comments

Post a Comment