THE HISTORY OF DEATH IN AMERICA

Death is not a pleasant subject for most of us unless you are Dr. Kervorkian. Early in my life I was sheltered from it. Until I was twelve no one had ever died that was close to me. I avoided the subject and I can remember riding by cemeteries or graveyards and I would turn my head in order to avoid looking at them. The first time that I saw a dead body was kind of by accident. My mom took me to the old Cosmopolitan funeral home on West End about where the big Barnes and Noble store is now, across from Centennial Park. It was 1960 and my grandmothers brother, Jake Frogge, had died. Mother knew that I was frightened at the thought of seeing a dead body so she left me in the lobby. I walked by the room that Uncle Jake was in and there he was, lying in his coffin. I was startled and quickly took a seat in the lobby while mother, with her guitar in hand, took a seat by the casket. She sang and played many of the old hymns while I sat and listened. I could listen to her sing all night.

My Uncle Buddy, who was my mother's younger brother, was a Methodist preacher in Eastern Kentucky and to supplement his income he worked part-time as a mortician. We were crazy about him and we would run excitedly to the front door of my grandmothers house whenever he drove down to visit her at Christmastime. The way that we acted you would think that he was Santa Claus himself. We would eagerly sit around the kitchen table listening to his stories about life among the mountain people of Eastern Kentucky. Eventually the subject would turn tho his job as a mortician and he would take pleasure in watching our reactions as he talked about what it was like to embalm someone who had drowned and been in the water for days, or had died from some disease like cancer that had ravaged their bodies. Or the victims of a serious car wreck or some other accident and how he had to make them presentable for burial. He would tell how he and the other morticians would sometime throw up because of the smell or the sight of the body when they received them. After the invention of super glue I learned how useful it was to the mortician in repairing damaged flesh. I had a hard time listening to these stories but I found them fascinating.

Then on January 16, 1963 I lost my parents. I worshiped my mother and the thought of seeing her dead body was more than I could bear. People would tell me "Gregory your mother looks so beautiful, you really need to go to the funeral home". Or "Gregory I am afraid that you will regret it if you don't go". My grandmother was my biggest defender and she would tell them to leave me alone. She would say "If he doesn't want to go don't try to force him". Mama didn't want to go to the funeral home either. That was what we called my grandmother. She had found my parents bodies and was still in shock. Mother was her daughter and I can only imagine how I would feel if one of my children died that way. I slept in a little bed over in the corner of my grandparents bedroom and she would sit beside me during those days of the wake and funeral. We would talk for hours late into the night sharing our grief together and finally I would drift off to sleep. This routine went on each night until two days after the funeral I woke up to find my grandmother missing. I was told that sometime after I had fallen asleep she had had a heart attack and was in the hospital.

It seemed like death hung over us that whole year of 1963. My Aunt Arda, who was my grandfathers sister passed away in September. President Kennedy was assassinated in November and we sat by the television for four unbelievable days. Then on January 26, 1964 my grandmother died after her fifth heart attack. Again, I could not force myself to go to the funeral home or to the funeral. We got a break over the next four years. Nobody died. Then we found out that my granddaddy had cancer and was dying. A cancer diagnosis in those days was pretty much a death sentence. He died in July 1968 and for the first time in my life I went to the funeral home to visit a dead person and I attended his funeral. I had been married for less than a month so I didn't want to show weakness in front of my new wife. Since then I regularly attend funerals and have been asked to sing at many of them. Funeral homes and hospitals are still not my favorite places to visit but I have come a long way since my younger days. I love to tour old cemeteries and grave yards looking for unique and historic graves. Nashville's Old City Cemetery and Mount Olivet Cemetery are my favorite cemeteries in Nashville. I enjoyed touring the old historic graveyards in Charleston South Carolina when I pulled a Guard summer camp there in 1989.

There have been various traditions surrounding death in America that go all the way back to Colonial days. Until fairly well into the Twentieth Century death touched just about every family on a fairly regular basis. Life expectancy varied. For example a slave's life expectancy was shorter but it was about 40 years old for White Colonials and has slowly risen since then gradually to the point that for women and men it is over 70 years now. Children died like flies from childhood ailments and the death rate was fairly high even into the 1900's. A puritan man named Samuel Sewall wrote, following the death of a daughter, that he spent all of Christmas day in her tomb. He said that" it was an awful but pleasing treat". In the Colonial days funerals were stark but social occasions. Women prepared the corpse. Dressing it in it's Sunday best and slipping it into a shroud of waxed linen and wool soaked in alum. Then later on carpenters began fashioning pine coffins to bury the dead in. After a while they got the idea to cut the top section of the lid off the coffin so visitors could view the remains.

By the 1830's mourners wanted something finer and coffin makers began making more elaborate coffins. Some were made out of metal, marble and cast cement. By the 1840's cemeteries became fashionable because graveyards were considered an eyesore. Patents were awarded on specialty model coffins. One was called the "torpedo model" that was designed to explode in the event that grave robbers tampered with the coffin. Getting to the grave required the service of bearers and later hearses. The ones who managed the pall were of course called pallbearers. The pall was a cloth covering over a coffin. The under bearers were the ones who did the real work by carrying the coffin. Somehow over the years the under bearers have come to be called the pallbearers.

Early hearses were simple wheeled wagons that might be pulled by men or a horse. Over time they became more elaborate with curtained windows, funerary urns, and tasseled swags as decorations. The more elaborate hearses required two horses and sometimes matching pairs of high steppers. Although funerals could be solemn occasions they were sometimes upbeat affairs. One minister made a funny gaffe by saying that "This is only a shell, the nut is gone" Attendees might be given souvenirs like a ring, scarf, gloves, and a bottle of wine. Rings and gloves were the favorites and ministers collected these things by the hundreds. Then there were dead-cakes that were given to the mourners. A type of cookie with the deceased initials baked in. By the late 1800's professional undertakers took over the business of handling funerals. The old coffins were replaced by caskets with quilted velvet interiors, heavy silver hardware, and rare woods that were supposed to last longer in the "harsh realities of the grave" .

In 1831 the so-called rural cemetery movement began with the development of the Auburn Cemetery in Boston that was more like a park than a cemetery. One visitor said that "A glance at this beautiful cemetery, almost excites a wish to die". It was built on 72 wooded acres. It was a popular place for lovers, families out for a carriage ride and sightseers to go on a sunny day. Small grave yards and Church grave yards were called bone yards and considered blights on society and hazardous to health. Nashville's City Cemetery was established in 1821 and because this cemetery had no room to expand Mt. Olivet was founded in 1856. This cemetery was much like the Boston Cemetery. At the time it was founded it was a rural area. My Aunt Didi and my mother grew up on Hermitage Avenue just down the street from Mt. Olivet. Didi said that Mt. Olivet was a popular picnic spot and they would go there on Sundays just to walk through the cemetery for recreation.

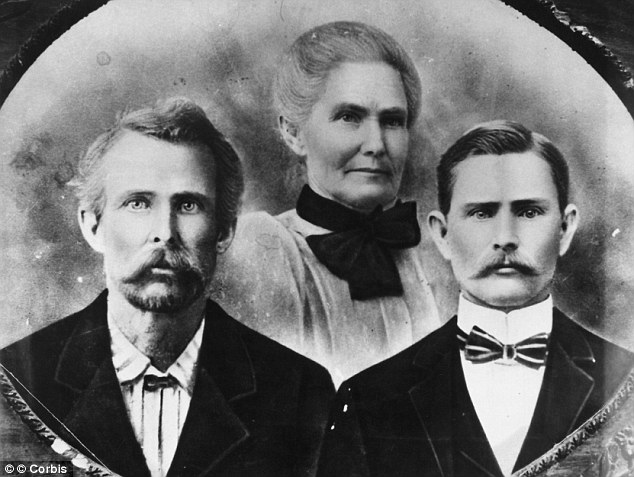

There was also a mourning etiquette developed in the 1800's. If a woman lost her husband she didn't leave the house for a month. She might remain in deep mourning for two years. The loss of a parent or child required one year. grandparents, siblings, or anyone who left a inheritance got six months. Aunts, uncles, nieces and nephews got three months. The "widows weeds" or clothing were of course black. After a year she could change to something glossy like silk in shades of dark purple and grey. She wore a black bonnet with a black veil for three months, then trail it down from the back of the bonnet for another nine months. Men showed their grief for a somewhat shorter time than women. They wore black suits. Toward the end of the century the rules eased as far as showing your grief publicly. One of the most bizarre things to come out of the 1800's was the post mortem photograph. Many times people did not have a picture of their loved ones in life and the only picture they might be able to get was in death. This seems to have been a lucrative occupation for them. They would go to great lengths to prop the deceased up with a metal stand or pose their body either alone or with live loved ones. Some of the deceased were even in various stages of decomposition.

|

| Post mortem photo |

It became popular to make mementos out of the deceased persons hair. A lock of hair might be preserved inside a locket. Bracelets were made from plaited hair. Elaborate necklaces, broaches, rings, fob chains, charms and ear rings were made from the hair of the dead. Mourning pictures painted by mostly teenage girls depicted scenes of weeping mourners. In many cases the deceased hair was ground up and used as pigment for the paint. Last but not least I wanted to talk about military traditions regarding death. In the Napoleonic Wars of the late 1700's and early 1800's soldiers bodies were covered with flags and removed from the battlefield on caissons. Two wheeled horse drawn carts to transport ammunition for artillery. The American tradition is to place the blue field of the flag over the soldiers left shoulder on top of the casket. Civil War General Daniel Butterfield wanted a bugle call to replace "Lights Out" that ended every day in camp. He worked out the call with a bugler named Oliver Norton. It probably got it's name "Taps" because it was still recognizable when tapped out on a drum. Taps became popular with the troops and over time was used at military funerals.

The 21 gun salute derived from British naval custom. Originally it was a 21 gun salute from artillery batteries reserved for honoring presidents, former presidents, and heads of foreign governments. The missing man formation goes back to World War I and started by the Royal Air Force. More than likely the custom arose when British pilots would fly over their home place after a mission so ground crews could see how many planes were missing and the condition of the surviving planes. Americans first used the formation in 1938 Usually four aircraft fly over the funeral site and one plane pulls away, sometimes flying west toward the sunset, to symbolize the loss of a comrade.

|

| Nashville City Cemetery |

|

| Nashville's Mount Olivet Cemetery |

Comments

Post a Comment