WILLIAM HOLLAND

There are two graves outside of the Hazen Brigade monument at Stones River. One of them belongs to William Holland. His name was Harlan but when he joined the army they recorded his last name as Holland and he apparently kept that name the rest of his life. The other William Harlan who I had the pleasure of meeting in the 1970's, was the grandson of William Holland and he served in World War I. I asked William one day if I could hunt Civil War relics on his property. He told me the story of how he had found relics by the bushel when he was a kid. William used minie balls as fishing sinkers. The following is the story of William Harlan's grandfather William Holland. Like many Civil War soldiers, William Holland left very few records about his life. What we know about him comes from his government pension file, which is enough to tell his story with some details. By his own account, William Holland was born a slave near Haydensville, Todd County, Kentucky in the mid-1820s. Holland was unable to read or write, and like most slaves, had little or no formal schooling. When he was an adult, he stood 5’3” tall, with dark eyes, a dark complexion and dark hair. Before the Civil War, Holland worked as a field hand for his owner, Benjamin Harlan of Maury Co. Tennessee. When the Union army came through Tennessee, William Holland’s life changed forever. He escaped to the Federal camps in search of his freedom and likley worked as a laborer.

|

| The Harlan plantation in Columbia Tennessee |

In 1864, William Holland joined the Union army as a private in the 111th Regiment of the U.S. Colored Troopers (USCT). For six months, in 1864, Holland’s unit guarded railroads in middle Tennessee and northern Alabama. In September 1864, Confederate soldiers under General Nathan Bedford Forrest attacked the fort held by Holland and his unit. The success of Forrest’s attack forced almost a thousand Union soldiers, including William, to surrender. As a prisoner, William Holland was assigned to Dr. James Cowan, General Forrest’s chief surgeon, as a “waitman” or servant. He remained with Forrest’s soldiers for three months, until after the Confederates were defeated at Franklin and Nashville. In early 1865 Holland somehow made it back to Union lines. Unfortunately he didn't leave any details about his time riding with Forrest’s raiders. We can only assume that he spent most of his time tending to the sick, dying and wounded and maybe to Dr. Cowan’s personal needs. How Holland got away and rejoined his unit also remains a mystery. After rejoining his unit, William Holland helped to create the Stones River National Cemetery under the supervision of Chaplain William Earnshaw.

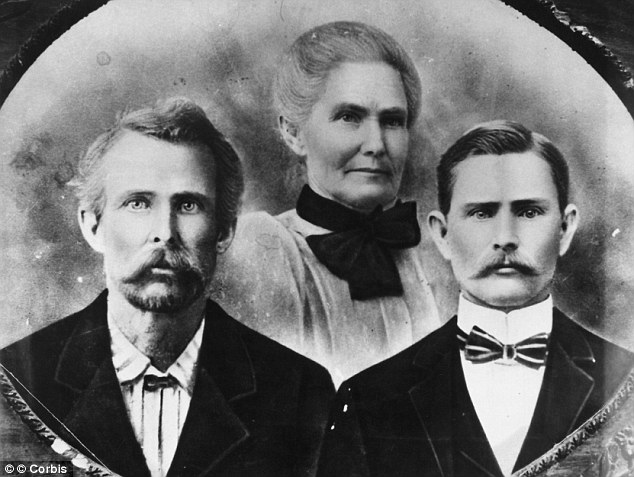

Until their Army service ended in 1866, Holland and his fellow black soldiers reburied the remains of thousands of Union soldiers and began building a stone wall surrounding that hallowed ground. After the Civil War William Holland worked as a laborer and was paid one dollar a day for his work. Holland was thrown from a wagon in the early 1880's while carrying a "brush load" of tree limbs and was dragged by a mule, hurting his left ankle and badly spraining his right shoulder, arm and hand. His days as a laborer were over. Hollands doctor, J.F. Byrn, wrote that since these injuries were of a “serious character” and caused pain in his joints, Holland could not work at the cemetery or do any hard work at all after the accident. With two young children at home, he must have struggled to provide for his family. William Holland lived at the cemetery for a year, then in 1867 moved to his own property just down the road. In his new house, Holland raised a family. Unfortunately, William’s first wife, Eliza, died in 1868. He remarried in 1871 to Ruth Miller Holland, who gave birth to two children—Josephine in 1872 and William in 1874. Both children lived to be adults, but Ruth died in 1878 leaving William to care for both of their children alone. William Holland was born as another man’s property. After a lifetime of hard work and service to his country, William was buried on his own property. Continuing his family tradition, Holland’s grandson William Harlan served in World War I and was buried next to his grandfather in 1979.

This land was owned by their family until 2001 when it was sold to the Park Service. William Holland's story of transition from slave to soldier to property owner and citizen represents the stories of four million slaves who gained their freedom as a result of the terrible sacrifices exacted by the Civil War. Together, these two men’s graves show the sacrifice made by blacks to support and defend our country. The Hollands were part of a thriving black community centered on the national cemetery. Most of the people living there were veterans of the 111th United States Colored Infantry and their families. The community was aptly named Cemetery and included farms, homes, churches, and schools.

|

| Freedman cabin in the Cemetery Community After the Civil War |

|

| A freedman's cabin north of William Holland's land |

|

| The William Holland Farm |

Comments

Post a Comment